Antonio Tsialas Cornell student death autopsy reddit obituary update

Drunken Hazing, a Fatal Fall, and the Silence of a Cornell Fraternity

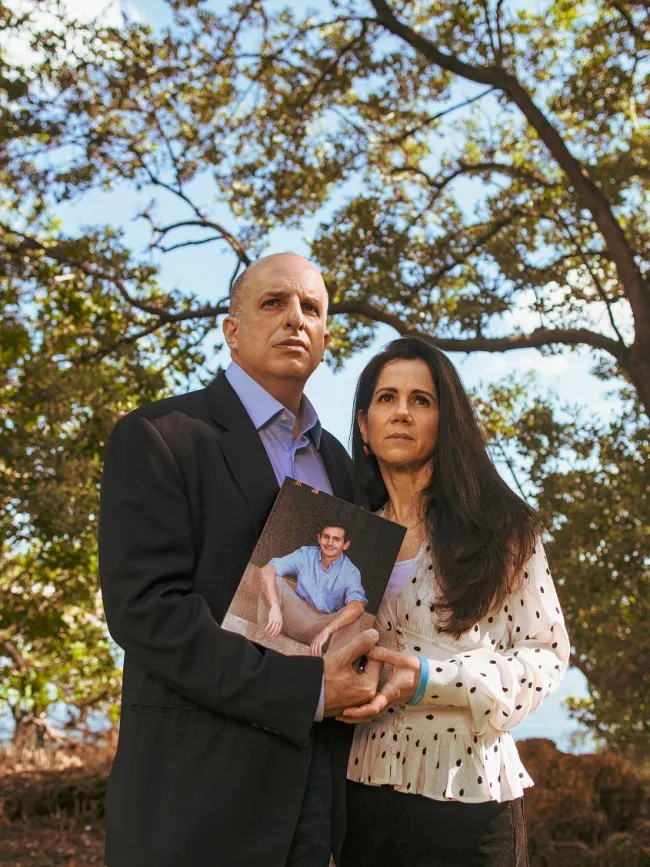

Antonio Tsialas had a fantastic first year of college. The fraternity that recruited him then closed ranks after he was discovered dead in a gorge. It's quite a mystery as to what happened.

Flavia Tomasello was overcome by the stench of alcohol when she approached the fraternity house where her missing son had last been seen at Cornell University. He was supposed to meet her at the campus bookstore that morning for parents weekend, but he never showed up. He was also not answering his phone at 10 p.m. His buddies hadn't seen him since the morning.

Fraternity brothers had driven hundreds of freshmen to the brick frat house on the Ithaca, New York, campus the night before and ushered them through seven rooms, each with its own alcohol-fueled challenge: shots in one, beers in another. The recruits were required to share a bottle of vodka in one bed. Some people puked and passed out.

Ms. Tomasello's uncle, Antonio Tsialas, an 18-year-old from Miami who had joined a club soccer team, started taking finance courses, and already found a job as a campus tour guide, was among the freshmen urged to drink at the Phi Kappa Psi party that night. A young woman confronted Mr. Tsialas at the frat party, announced that he was not intoxicated enough, and poured vodka down his throat, according to another freshman.

When Ms. Tomasello arrived on Friday evening searching for her son, the Phi Kappa Psi brothers did not mention it. Instead, the fraternity brother who had invited Mr. Tsialas to the party said that he had only caught the tail end of it because he had spent the night at the library. Mr. Tsialas had gone to another party after that, according to the fraternity's president.

Investigators later discovered that neither assertion was valid.

Ms. Tomasello pleaded with the fraternity brothers for information that night in October 2019, her son was found in a shallow pool of water at the bottom of a large ravine nearby, his head shattered, ribs broken, and enough alcohol in his blood to suggest he was drunk when he died.

His parents are also trying to figure out what happened more than a year later. Fraternity brothers who refuse to speak, a campus police department unprepared to investigate, and a university willing to mark their son's death as not suspicious have stymied their quest for answers, they say.

Ms. Tomasello recently said, "I'm just a mother who wants to know what happened to her son." “We don't worry about anything else except figuring out what happened to Antonio and stopping it from happening again.”

The chief of the Cornell University Police Department declared in November, more than a year after Mr. Tsialas' death, that he was closing the investigation, despite the fact that few of the key questions concerning Mr. Tsialas' death had been addressed. The local prosecutor confirmed that no charges will be brought against any fraternity brothers.

In a statement, Cornell Vice President Joel M. Malina said he supported the Cornell Police Department's investigation and that the university had taken steps in recent years to make fraternities safer, including suspending or restricting the activities of 28 Greek organizations. Following Mr. Tsialas' death, Cornell officials found Phi Kappa Psi guilty of hazing, alleging that the fraternity had made it clear that recruited freshmen were "ordered" to drink excessively, and the university disciplined 39 students involved in the party with a number of penalties, including at least one suspension.

The New York Times pieced together this account of Mr. Tsialas' last night and the investigation into his death by looking through photos, letters, text messages, and hundreds of pages of other documents, including the 158-page case file from the campus police department. These records, as well as interviews with more than a dozen people involved in the case, demonstrate how fraternity members withheld details about the party, making it impossible for the cops to find out what happened.

Mr. Tsialas' death, for his parents, is a nightmare illustration of the dangers posed by the tradition, secrecy, and privilege that pervades many American fraternities, and it came during a rash of disturbing fraternity-related deaths around the country in the fall of 2019 — the last full semester before the coronavirus disrupted student life.

At Cornell, the outpouring of sorrow soon turned to rage at Phi Kappa Psi, one of the university's more than 50 fraternities and sororities. Cornell subsequently kicked the fraternity off campus and revised some of its Greek life rules, citing Mr. Tsialas' attendance at an illegal gathering.

Mr. Tsialas died as a result of "a fall from height," according to the medical examiner, and it was listed as an accident on his death certificate. But it's still a mystery how he got to the gorge's edge and plunged to the bottom.

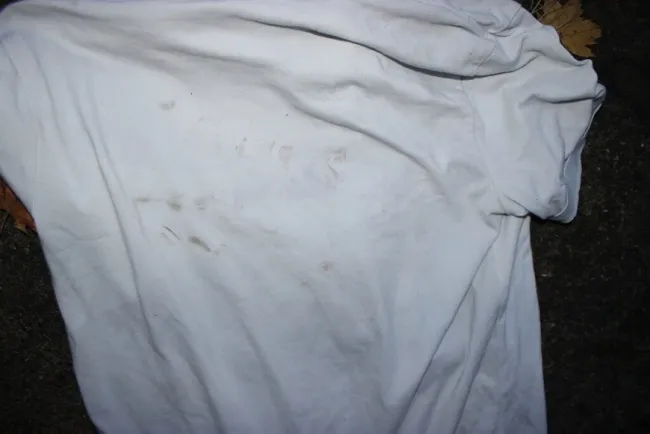

There were up to 100 people at the Phi Kappa Psi building, but no one claimed to have seen him leave. Mr. Tsialas is believed to have left the party and walked to a secluded area overlooking one of Ithaca's popular gorges, about a 10-minute walk from the fraternity and away from any route to his dormitory, according to Cornell officials. A waist-high stone wall stood between him and the gorge, with the roaring sound of a waterfall on the other side. His white polo shirt, stamped with what seemed to be a shoe print and stained with blood, was discovered at the top of the ledge he dropped from. He was also wearing a black sweatshirt, which was odd. His phone was misplaced and never found.

Ms. Tomasello and her husband, John Tsialas, are still baffled as to how they went from celebrating their eldest child's success at a prestigious university to identifying his broken body in a hospital in just a few days. They want to know why he was at the cliff's edge, how he plunged to his death on the rocks below, and whether someone was with him or saw him on his way there.

The cops haven't said if any of the fraternity brothers know the answers, but if they do, they're not telling. Many parents of fraternity brothers hired attorneys to keep the cops from questioning their sons. Those who did speak provided little detail. Investigators say they lied in some cases.

In October, we celebrate Christmas.

On Thursday, Oct. 24, 2019, Ms. Tomasello flew into Ithaca for Cornell's freshmen family weekend, eager to see her son and meet his new friends. Mr. Tsialas called home often in his first few weeks, even helping his younger sister and brother with their homework over the phone.

Ms. Tomasello and her son reunited at a Thai restaurant downtown the night after she arrived. Mr. Tsialas was embarrassed when she asked too many people to take their photo that evening, but he complied.

Mr. Tsialas told his mother about 8 p.m. that he needed to return to campus to work on a project and that he would see her in the morning. Fraternity brothers had actually told the invited freshmen that they would pick them up at 8:30 a.m. on campus. Mr. Tsialas got into a Lyft and rode west, carrying a box of cereal that his mother had purchased for him.

Fraternities are prohibited from recruiting freshmen before their second semester at Cornell, but the prohibition is so often violated that it has earned the moniker "dirty rush." Christmas in October was the name of the party that night, and it was not the first time Phi Kappa Psi had hosted it.

Mr. Tsialas was assigned to a group of other freshmen and led through Christmas-themed rooms full of alcohol once he arrived at the fraternity house. A fraternity brother warned them not to tell anyone they were at the party, and he made it clear that no one was obligated to drink, but some freshmen later informed the police that they were pushed to do so. One freshman who was determined not to drink too much ended up puking in the frat house trash can.

Few people said they saw Mr. Tsialas at the party. Those who knew him described him as cheerful, social, and soon drunk.

Mr. Tsialas started searching for Felipe Hanuch, a sophomore fraternity brother who had invited him to the party and had played with him on the club soccer team. Around 10:15 p.m., Mr. Tsialas called Mr. Hanuch twice, each conversation lasting about two minutes.

According to the police file, Mr. Hanuch told the cops the next day that Mr. Tsialas had called him from a bathroom and asked him to come to the party. Mr. Hanuch also claimed to have stayed at the library until midnight, long after the party had ended, but an officer wrote in his file that he assumed Mr. Hanuch was “lying about his whereabouts.” Mr. Hanuch had been posted outside the house as a "sober monitor," one of several people who were expected to keep an eye on attendees, according to several fraternity members. Mr. Hanuch hired a lawyer after his initial interview and never spoke to the cops again. Mr. Hanuch refused to speak with me when I called him recently.

The Tompkins County district attorney, Matt Van Houten, said in an interview that the fraternity members' silence had angered him, despite the fact that they were within their rights not to talk with the cops.

He said, "It seems to me that all of these kids who went to law school have had a total moral collapse." “It's so unbelievably selfish to cover your own ass at the cost of these parents who are distraught, losing their oldest son and a girl in that way.”

Mr. Tsialas called Pierce Lukonaitis, who lived in his freshman suite and was one of his closest friends on campus, shortly after his calls to Mr. Hanuch from the crowd. Mr. Lukonaitis soon realized Mr. Tsialas sounded inebriated. Mr. Tsialas left a voice mail message on his mother's phone at 10:29 p.m., but it was just echoes and background noises; she did not know he had called until the next day and believes it was a pocket dial.

As the party came to a close, a voice mail message was left.

At 10:29 p.m., these garbled sounds from Mr. Tsialas' phone were left in his mother's voice mail inbox. She thinks the phone call was a fluke.

About that time, his iPhone most likely died, making it difficult for the cops to trace him. The jumbled video on his mother's phone is the last time he was registered.

‘There was no foul play.'

Ms. Tomasello was running late to meet her son the morning after the party, so she texted him as she drove to campus from her hotel: “Good morning boy, hope your class went well this morning.”

Mr. Tsialas was not at the bookstore where they had arranged to meet when she arrived, and he did not return her calls. She texted, “Antonio, could you please respond?” She went to his dorm, but he was nowhere to be found. She became frightened and went to the campus police station.

Fraternity members were concerned about getting in trouble with their group when news of Mr. Tsialas' disappearance spread, according to the police report. Mr. Tsialas' friend and suitemate, Mr. Lukonaitis, later told investigators that the fraternity president, Andrew Scherr, had called him that morning and informed him not to inform anyone that Mr. Tsialas had attended the party. Mr. Scherr, who later met with police investigators extensively, declined to speak to The New York Times.

Mr. Tsialas' body was discovered by flying a drone over the gorge on Saturday, two days after the group. Ryan Lombardi, a Cornell vice president, said an investigation was underway and told the campus that "no foul play" was found in an email sent to students hours later. When a body is pulled from one of the many rugged ravines that give the city its motto, "Ithaca Is Gorges," Cornell officials use the term in a number of circumstances, including when a student's death is ruled a suicide.

However, Mr. Tsialas' parents believe it was premature to presume a fatal accident or suicide in this situation, and they suspect that the Cornell Police Department followed suit, resulting in mistakes in the investigation.

The police did not attempt to match dirt stains that looked like a shoe print on Mr. Tsialas' shirt to anyone, despite the fact that they may not match the shoes Mr. Tsialas was wearing.

One woman who lives near the overlook told The New York Times that the police never approached her, raising concerns about how deeply they canvassed the area, according to the family's lawyer.

There were other anomalies as well. According to the police report, as the search for Mr. Tsialas continued the day after the party, campus police officers advised the fraternity president to have members search their house for “anything that could assist” in locating Mr. Tsialas. After Mr. Tsialas' body was found, police officers did not complete their own extensive search of the fraternity until the next day.

When a campus officer looked at drone footage of the gorge and saw what he thought was a phone, the cops never went looking for it. According to the police register, the place was too icy to enter by that time, in December 2019, but they never returned when it thawed.

Mr. Tsialas' parents' lawyer, David Bianchi, said, "It's inexcusable for a big university in charge of a death investigation to not do even the most basic stuff." Given that Mr. Tsialas' body was discovered on city property and that the city police had traditionally investigated unnatural or suspicious deaths even though they occur on Cornell's campus, he had pushed for the Ithaca Police Department to take over the investigation. They just played a supporting role in this situation.

The head of the campus police department, David Honan, has turned down several offers to be interviewed for this post. Mr. Malina, the university vice president, defended what he called a "exhaustive" investigation, adding that police officers questioned about 150 people. He speculated that the campus police may have led the investigation simply because they were the first to investigate Mr. Tsialas' disappearance.

He reported that the mark on Mr. Tsialas' shirt was not clearly a shoe print, and that the police had repeatedly asked residents in the area where Mr. Tsialas died to come forward with any details. Mr. Malina said that it was never clear if the item seen on the drone footage was a smartphone, and that having the phone “was not deemed necessary” once it was safer to enter the gorge since some documents had been collected via search warrants.

Mr. Malina acknowledged that the investigation had been complicated by fraternity brothers' lies and silence. However, he also blamed Mr. Bianchi, claiming that his case against Cornell on behalf of Mr. Tsialas' parents, which was filed months after the investigation began, had prompted more fraternity brothers to remain silent.

Mr. Malina said, “It's most probable that Antonio walked to the overlook, and there's no proof that anyone else was there with him.” Cornell had renamed its annual National Hazing Prevention Week events after him, he said, and the university "continues to mourn his tragic death."

An inquiry is now complete.

The first recorded fraternity hazing death in the United States occurred at Cornell in 1873, when blindfolded freshman Mortimer M. Leggett died after falling into a gorge with two fraternity brothers who were supposed to be guiding him. After Henrietta Jackson, a chef, was fatally poisoned at Cornell, presumably by a sophomore who had been hoping to annoy freshmen with chlorine gas, New York passed what is thought to be the first state anti-hazing law about 20 years later.

George Desdunes, a sophomore from Brooklyn, died at Cornell in 2011 after being tied, blindfolded, and encouraged to drink during a ceremony. Three students were arrested and charged with hazing by the Ithaca Police Department; all three were acquitted.

Mr. Van Houten, the district attorney in Mr. Tsialas' case, said there wasn't enough evidence to press charges under the state's misdemeanor hazing statute, which would require him to show that the fraternity brothers did something "intentionally or recklessly" when initiating Mr. Tsialas that put him in danger. Legal experts agreed that Mr. Van Houten would have had a difficult time obtaining a conviction, and he stated that he had little interest in charging the students with low-level alcohol offenses.

Mr. Van Houten still has one choice for getting students to chat, but it comes with its own set of risks.

People called before a grand jury in New York could be forced to testify, but only if they are granted broad immunity. Mr. Van Houten believed that summoning a grand jury without evidence of a crime would be a "abuse" of the system, and that since grand jury hearings are essentially confidential, the testimony would certainly never be made public anyway.

Even, anything is preferable to giving up for Mr. Tsialas' kin. The university developed a scholarship in their son's name as part of the settlement in their case against Cornell. Mr. Tsialas' parents have also been on a quest to discourage college hazing, all while hoping that someone could come forward with details about Antonio's last moments. They have a $10,000 lead bid on the table.

Ms. Tomasello said of the fraternity brothers, "We don't want to see these kids in prison." “From the bottom of our hearts, we tell you that we don't. But we'd like to learn more.”

They are concerned that now that the police investigation has concluded, the campus will easily forget Mr. Tsialas and the warning his death brings. With the start of the spring semester last month, Cornell's fraternities started recruiting their newest pledge class.